‘The University of Cedar Rapids'

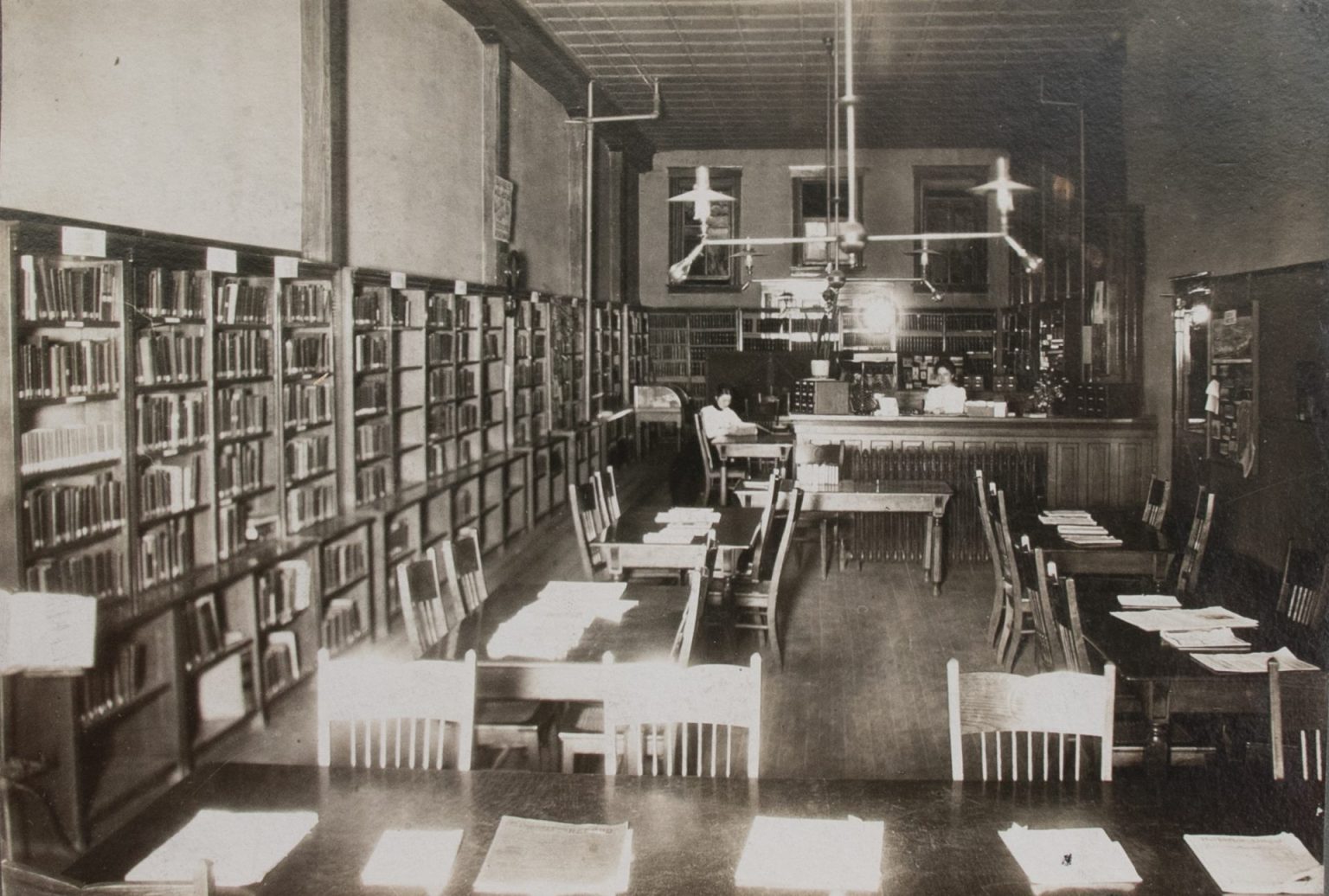

The day the Cedar Rapids Free Public Library opened its doors to the public for the first time, on January 15, 1897, The Gazette reported on the event, describing “throngs of people eager and glad to be there.”

“The university of Cedar Rapids, the new free library, was thrown open to the public last evening,” the article said.

Though that first library was small, just a room in the Granby building downtown, at the corner of Second Street SE and Third Avenue SE, it’s addition to Cedar Rapids life was momentous. It was called the free library to differentiate it from the ways people accessed books before - from private libraries, which often had membership fees, such as a rental library at the YMCA, and a Library Association before that. In 1885, the Masonic Library opened, and numerous literacy clubs and societies were formed.

‘Won by the Women’

The city was rapidly growing; the population doubled between 1880 and 1890. In 1895, Ada Van Vechten organized eight women’s literacy clubs into the City Federation of Ladies Literacy Clubs. The women of the federation campaigned to establish a library, organizing concerts and circulating petitions.

While women could not vote generally, in 1894, Iowa became one of only two states to pass legislation allowing women to vote on limited tax issues, including library levies. The City Council put the matter to a public vote on March 2, 1896. The results were 1,105 votes yes to 1,046 no. The library was approved by just 59 votes.

The Gazette reported returns showed half the men who voted didn’t vote on the question at all, and speculated the vote may be challenged on the grounds that “the women are illegal.”

“Had it not been for the efforts of the women themselves who voted in every ward in the city, the proposition would undoubtedly have been lost,” the article said. The mayor asked Van Vechten to choose the new library’s first Board of Trustees. The four women and five men of the new board elected Van Vechten their president. The Gazette dubbed her “the mother of the library.”

The first librarian, Virginia Dodge, was a woman, as were all the head librarians through 1949. Dodge was from Oak Park, Ill., and had studied at Wellesley College and completed library school at Armour Institute. She opened the new library along with an assistant, Kathryn Canfield, and an apprentice.

Early Years

The first book added to the new library’s collection was Eugene Field’s The Love Affairs of a Bibliomaniac, and the first book borrowed was Van Dyke’s Art for Art’s Sake. From an initial collection of 1,325 books, the library quickly grew. It needed to – Cedar Rapids residents were enthusiastic borrowers, checking out more than 1,500 titles in the first two weeks.

Virginia Dodge left Cedar Rapids in 1899, and Harriette McCrory became librarian. She organized reading clubs for children, along with a club for boys that gathered at the library in the evenings. Dubbed “The Knights of the Round Table,” the boys learned clay modeling, carving and whittling, and printing.

In 1900, the library moved to a larger space in the Dows Building, at the corner of Second Avenue and Third Street downtown. Meanwhile, the Board planned for future growth, sending a letter to business tycoon Andrew Carnegie in 1901, asking for his philanthropic support. Carnegie, known for funding the creation of libraries across the country, sent Cedar Rapids $75,000. A location on Washington Square, now known as Greene Square, was selected in 1903. Construction started in 1904, and the new building opened on June 24, 1905.

Ada Van Vechten lived to see her dream realized when the new building opened. In November 1905, she became ill and died at age 64. The library closed for the day of her funeral.

Library Access for All

From the first day the library opened, getting books to as many people as possible was a guiding principle.

“Do you realize that the library building is the only absolutely neutral ground in the city? Here there are no distinctions of age, race, or religion. Every one, young and old, should feel at liberty to come here freely every day in the year,” Librarian Harriet A. Wood wrote in the 1907 Annual Report

In 1904, the library established special programs for the blind, and farmers in the area were given resident privileges. Books were acquired in different languages, and many were donated, including a Bohemian collection for the town’s Czech and Slovak population.

Serving children was a primary concern, and the library had trouble keeping up with young readers. So popular were the books in the children’s collection that a program of grade school children visiting the library in 1889 could not be continued due to a shortage of books.

In the 1898 Annual Report, Librarian Dodge noted the library could not “buy enough books to keep the children, especially the boys, supplied with good literature, and it is very discouraging to see the boys, after waiting around the children’s shelves from 30 minutes to an hour, hoping some good book, unread by them, may come in, go away empty handed.”

In the 1911 Annual Report, the problem was noted again: “These books for the youngest readers are so popular that a new set is scarcely placed upon the shelves before eager children ask to take them home.”

By 1909, the library began looking for ways to reach new people, with books in schools, drugstores, and at factories. By 1911, books and magazines were available in the Quaker Oats women’s dining room, the T.M. Sinclair Packing Co., and the Williams and Hunting factory. Librarians also made an effort to visit rural areas.

In 1912, friends of the library lent a horse and automobile to allow a librarian to visit all the schools in the Cedar and Clinton townships with collections of books and to hold story times. The library supplied collections to schools throughout Cedar Rapids.

In the 1910s and 1920s, the library worked to expand outreach, creating library stations in neighborhood grocery stores, parks, and hospitals. They sent books to street railway conductor’s and motormen’s waiting rooms, and to a room used by telephone operators. In the summer, librarians took books and story times to parks. By 1918, the library was operating 22 stations. The library’s goal was to have books available “within easy walking distance of each section of the city.”

“To give the maximum of service, we must take our treasures to the people,” board President Luther A. Brewer wrote in the 1928 Annual Report.

Yarcho Grocery hosted a library station.

Kenwood Branch

In 1912, Kenwood Park, at the time a village between Cedar Rapids and Marion, contracted with the library for service, and a reading room was set up in a village church. The village would later move the library station to a building that also housed the streetcar waiting room, the village jail, and the councilmen’s meeting room, in the early 1920s.

In 1926, Cedar Rapids incorporated Kenwood into the city, and in 1929 the City Council approved funds to build a Kenwood park library branch at 3223 First Avenue, the site of the previous station. The Spanish adobe-style building opened in February 1930. The Kenwood Branch was remodeled in 1955, with a new brick exterior and updated interior, and then was expanded in 1963.

By 1992, the building was in need of remodeling to be in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, but the budget did not permit it. Instead, an East Side branch opened at Town and Country Shopping Center.

Pandemics Through the Ages

Long before the library would temporarily close and quarantine books at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cedar Rapids was dealing with public health concerns that impacted the library. In 1901, a smallpox outbreak led to book circulation stopping for three months and children being barred from the library. After the health department lifted the order and books were disinfected, many people were afraid to use them.

In 1914, an early winter diphtheria outbreak led librarians to fear all circulation of books would have to be halted again. Though cases dropped before that could happen, hundreds of books shared through one school building were called in under a quarantine order, and many books were destroyed for fear of contagion. Librarians sent some books ordered destroyed to the homes of those in quarantine.

Precautions were also taken during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. On October 15, 1918, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette reported, “Children are requested not to remain at the public library and read until the influenza epidemic is over. They may still draw books, but it is thought best not to keep the children’s reading room open. The library stations at Kenwood Park, Daniels Park, Sixteenth and at the Grant Vocational school will be closed until further notice.”

In 1923, the children’s library moved to the second-floor auditorium, as the first floor of the library grew over-crowded.

Running Out of Room

By the 1920s, the Carnegie library was already pressed for space. A movable wall extended the building into the alley, and the children’s room was moved to the second floor in 1923, taking over the auditorium space.

Cedar Rapids was growing quickly, and circulation of books grew quickly, too. During Librarian Joanna Hagey’s tenure from 1910 to 1939, the Cedar Rapids area grew to 60,000 people, an 83% population increase. Library patrons increased by 99% during that time. The library was hard pressed to keep up with demand.

In the 1926 annual report, Hagey wrote “There is urgent need for more space … the congestion is now embarrassing. The shelves are overflowing; it is difficult to keep books in their proper place.”

The Library During War

When the United States entered World War I, the library provided books to an encampment of service members at Cedar Rapids and shipped books to Cedar Rapids companies training at Camp Dodge in Des Moines.

The library reported a drop in circulation in its 1918 annual report and attributed it to more than 700 men being enlisted and women being busy with knitting and other Red Cross activities.

The second floor and part of the basement were converted to a Red Cross station, where citizens came to help make surgical dressings, take classes, sew and knit.

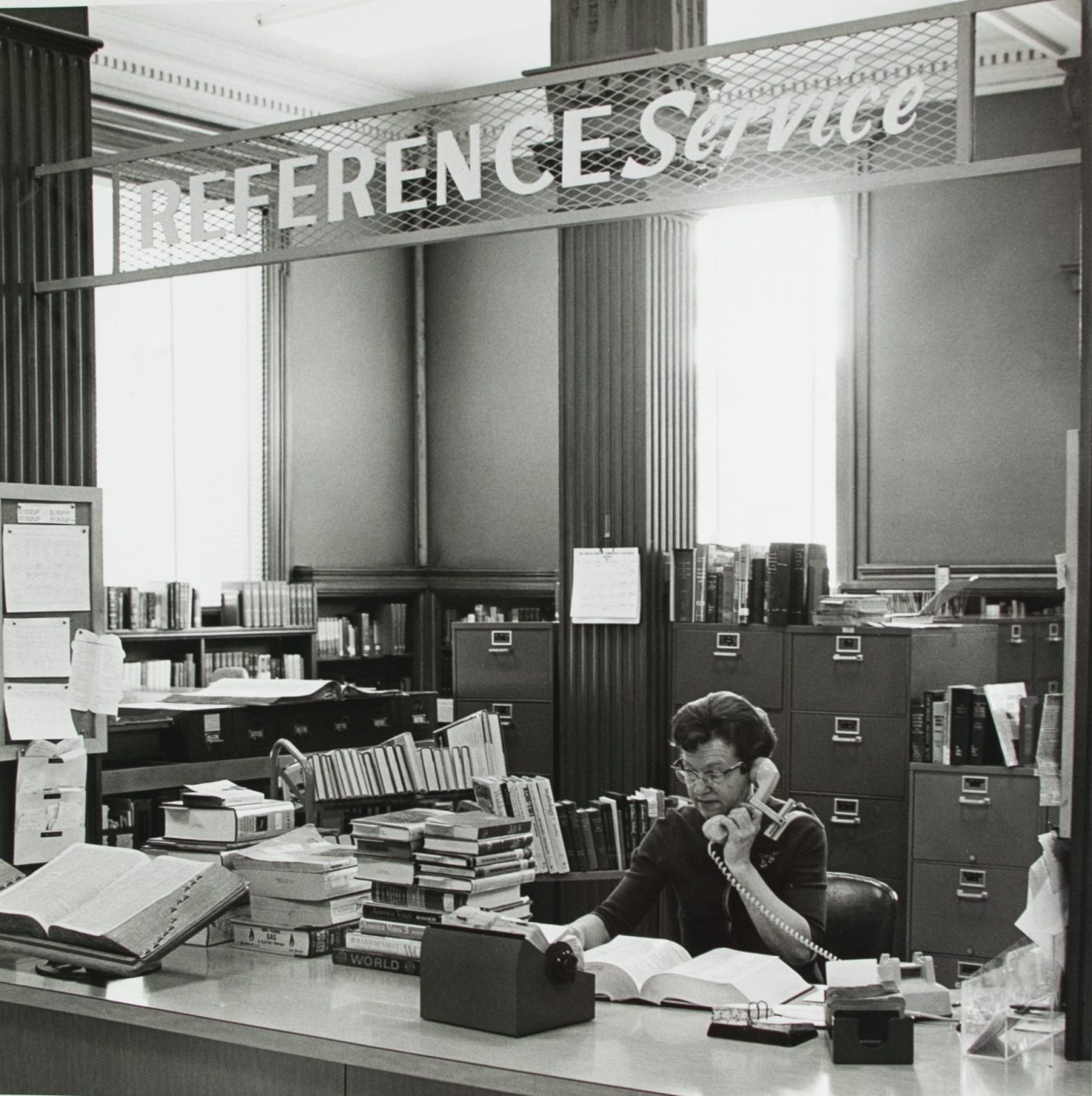

Circulation was up during the Great Depression in 1931, with mysteries, Westerns, and other popular fiction especially sought after. The reference desk had to limit the time allowed to use the dictionary, as radio contests were especially popular.

During the Great Depression, the library addressed community unemployment by hiring extra people to help with office work and cleaning. Federal Relief Workers, Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Works Progress Administration, and Civil Works Administration workers also completed building improvements, repairs, and other tasks at the library.

The reference desk was also pulled into service during World War II, when families of enlisted men would bring in letters from their loved ones. The men were not allowed to disclose their locations but would mention a sight they had seen or the plants and animals around them, and families came to the library, hoping for help deciphering these clues to where their sons and husbands were stationed.

In January 1942, the Victory Book Campaign began, with thousands of books donated for the armed forces out of Cedar Rapids. The library also stocked books on topics in high demand by patrons, such as civilian defense, victory gardens, aviation, and European history. Children could join the Army-Navy Reading Club and the Paratroopers Club.

On May 10, 1943, the library participated in a national commemoration of the 10th anniversary of a book burning under the Third Reich. Books by authors such as Carl Sandburg, Karl Marx, Thomas Mann, and Sinclair Lewis, all banned in Germany, were displayed.

Growing for the Future

The 1950s saw continued growth in the city, and at the library. In 1952, the library’s first bookmobile arrived, with six stops scheduled each week. It would take over for the library stations, and become busier than they had been.

The same year, an addition to the downtown library allowed the children’s department to move back to the first floor. A second addition followed in 1953, as the library circulated more than half a million books for the first time.

The library purchased a second bookmobile in 1954. A new tax levy paid for both the bookmobile and the additions.

In 1964, the library purchased a third bookmobile, expanding mobile service to Saturdays, with stops throughout the week in 19 neighborhoods.

The first two bookmobiles were retired in 1971 and 1972, as the Edgewood branch opened in 1971 at 221 Edgewood Road NW. The Friends of the Library later bought a Friendsmobile in 1978, which held 400 to 500 hardcover books and 700 to 800 paperbacks.

In his 1960 Annual Report, head librarian James C. Marvin reported “The decade of 1950-1960 saw the book circulation of the library increase 100 percent.” By 1964, circulation was at 958,000 items.

The library, built for a collection of 12,000 books and a population of less than 30,000 people when it opened, served a population of more than 100,000 people by 1969, and it held 150,000 books. The building was overcrowded, with thousands of magazines and books stored in the basement.

In 1969, a bond issue to add an extension to the library and open a west-side branch failed to pass – though it received a majority of the votes, it needed a super majority of 60% to pass. The same thing happened on bond votes over the next decade – five votes failed between 1969 and 1981.

Art in the Library

From the beginning, art was part of the library. In the early days, thousands of pictures were circulated, and the Carnegie building included an art gallery on the second floor, which the local Art Club used.

In 1906, the Public Library Art Association formed; membership cost $1, with the funds used to purchase art for the library. In 1907, the Art Club gave the Association a Charles Francis Browne oil painting, “The Shadowy Bank,” and the Association purchased a Ben Foster painting, “The Gathering Storm.”

That year a stained glass window was dedicated to the memory of Ada Van Vechten. The window was commissioned by friends after Van Vechten’s death in 1905 and designed and built by stained glass artisans, R and J Lamb, of New York City, in 1907.

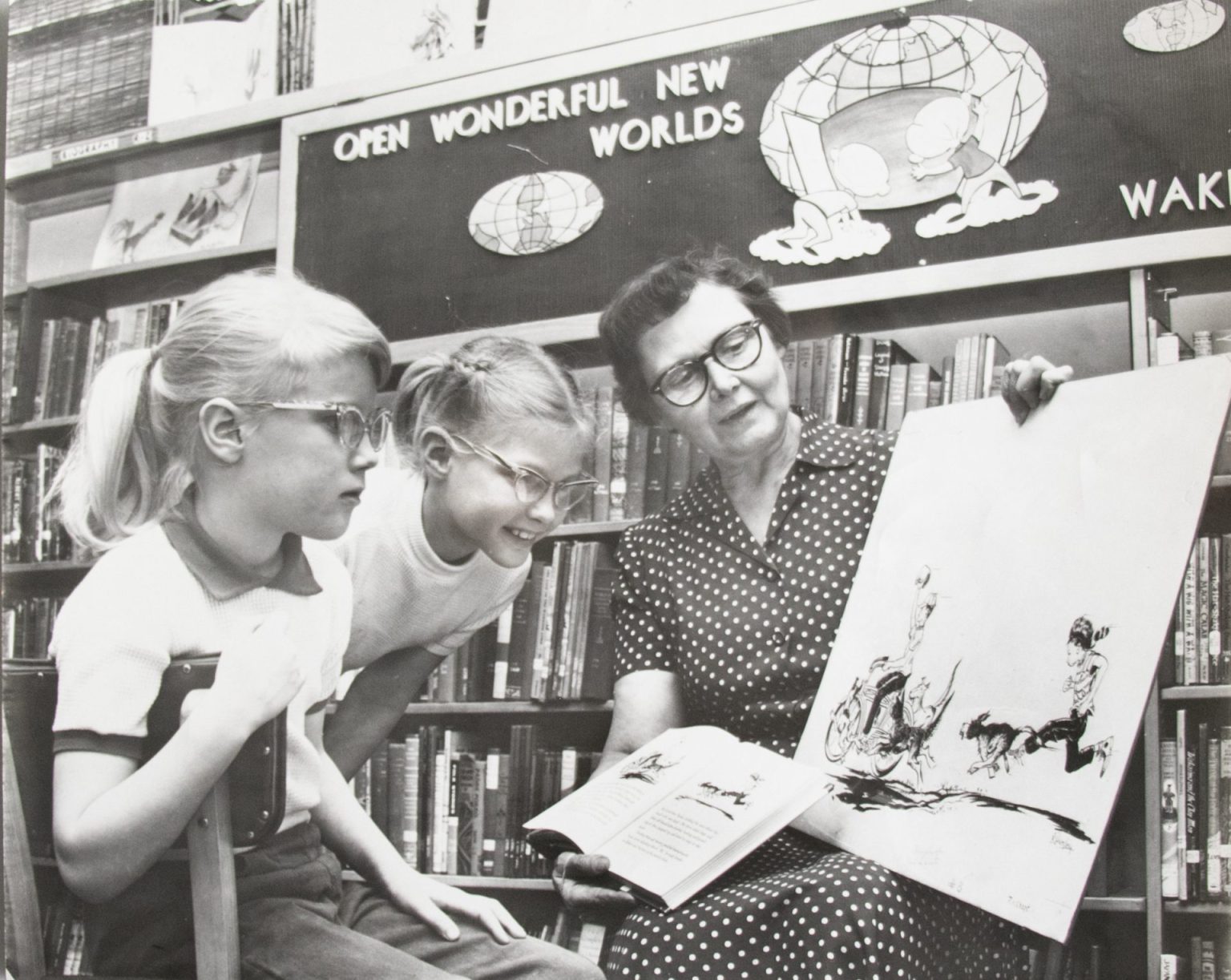

In the 1950s, children’s librarian Evelyn Zerzanek started writing to famous children’s book illustrators, asking if they would donate a drawing to the library.

The first came from Maurice Sendak in 1958, who drew a special illustration for a pamphlet, “All About Growing Up,” with book suggestions for children and parents. He would go on to illustrate bookmarks, letterheads, and more for the library.

The Zerzanek collection of illustrations eventually grew to hundreds of pieces of art, including watercolors, pen-and-ink drawings, pencil sketches, silk screens and color separations.

Eight Caldecott Medal winners were among the artists who donated, with many original pieces referencing the library directly. H.A. Rey sketched “Curious George” heading to the Cedar Rapids Public Library, and Sendak sent a drawing of children carrying a “Cedar Rapids Public Library” banner.

A New Building

In 1971, the Friends of the Cedar Rapids Public Library was founded, followed by the Metropolitan Cedar Rapids Library Foundation in 1972. Both would be instrumental is the effort to build a new library. In 1981, after the final bond issue failed, the Hall Foundation pledged a $6.8 million grant to fund the project.

The foundation’s grant came with the condition the city would issue bonds for the project and be responsible for securing the building’s site. The Library Foundation agreed to raise $1 million, and, along with the Friends, undertook a fundraising campaign that brought in $1.3 million in five months, with 18,000 donors contributing amounts ranging from 10 cents to $150,000 from an anonymous donor.

Ground was broken for the new building on Nov. 5, 1982, and the new 83,100 square foot building opened on Feb. 17, 1985, at 500 First St. SE. Cedar Rapids Mayor Donald Canney proclaimed 1985 the Year of the Public Library.

A new library branch opened in 1988 at Westdale Mall, replacing the Edgewood branch. It moved into a bigger spot in the mall in 2000. With the new downtown building came the move to a digital card catalog in 1985.

In 1991, the library offered access to the catalog for home use online. In 1992, the library offered internet access to patrons, who could create dial-up accounts in the building. The same year, it was declared the busiest public library in Iowa, circulating 12.6 items per capita, compared to the national average of 5.5.

In 1999, the Cedar Rapids, Marion, and Hiawatha libraries joined forces to create the Metro Library Network. Collection items are shared between the three library networks, giving patrons of all three towns increased access.

The Flood of 2008

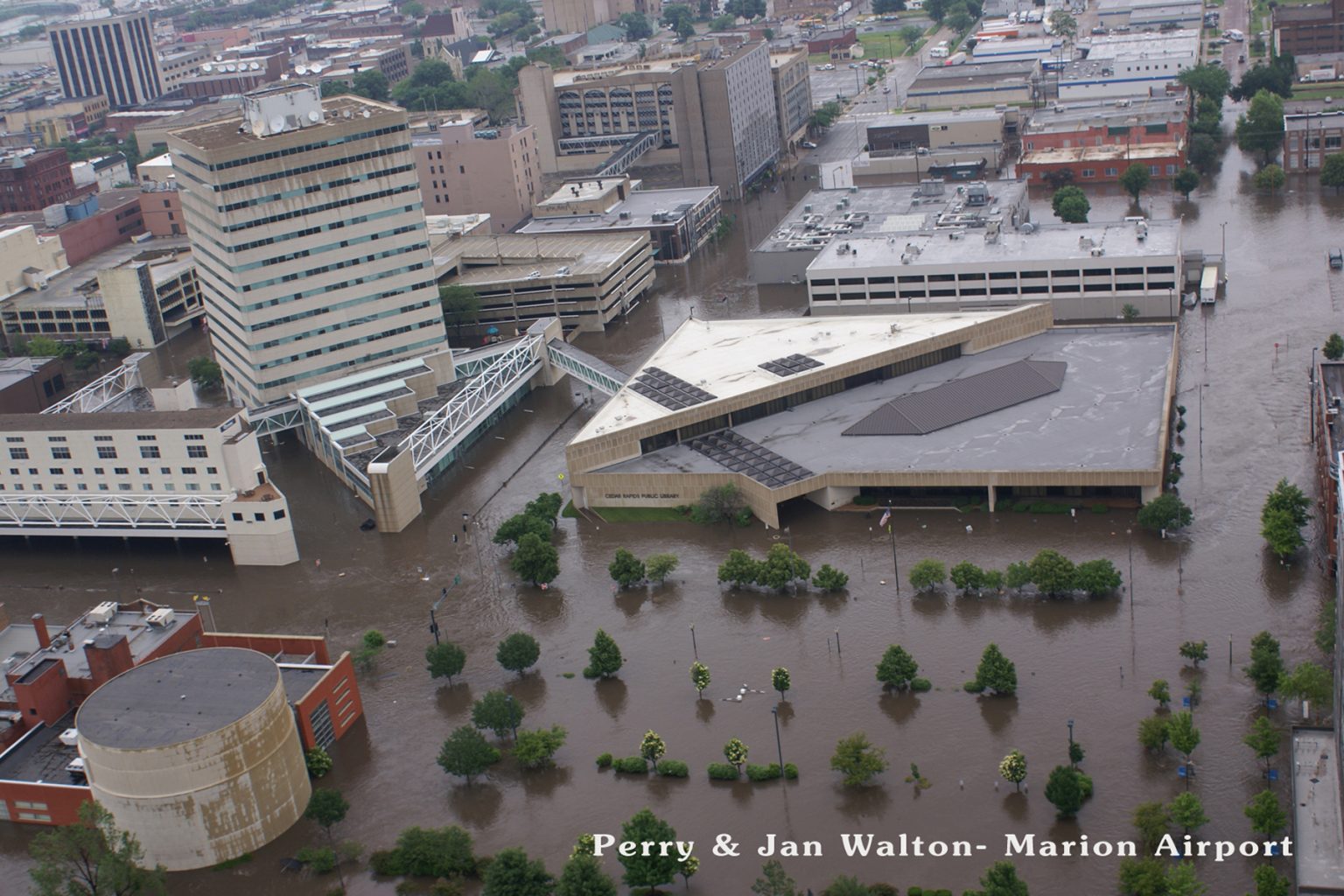

On June 12 and 13, 2008, the Cedar River rose, inundating 10 square miles of the city, including much of downtown Cedar Rapids. The Downtown Library was not spared. Water rose five feet on the first floor, destroying the entire adult collection.

The library lost about 160,000 books, movies, music albums, and other items, and the 85,000-square foot building had to be gutted. Staff had moved the Zerzanek collection and some other materials to the second floor, and books were moved off the bottom shelves, but the waters rose higher and faster than anyone anticipated.

On Feb. 23, 2013, Ladd Library opened to replace the Westdale location, named for Rockwell Collins test technician Marilyn Ladd, who left the library almost $750,000 when she died in 2012.

The new Downtown Library opened on Aug. 24, 2013. The project was funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the state I-JOBs program, the city’s local option sales tax for flood recovery, and donations – the Library Foundation raised almost $7 million in private donations from around 1,400 people.

Built to be Platinum LEED certified with geothermal heating and other energy efficiency systems, the building responded to the devastation of 2008 by seeking to mitigate future flooding with the succulent-covered LivingLearning Roof and permeable pavement that diverts water from the storm sewers.

“We believe that it stands as perhaps the best and most fitting symbol of a recovery that’s admirably focused on creating a more promising future for this city from the muck of its most difficult chapter,” a Gazette editorial about the new building’s opening read.

Looking to the Future

The last few years of the library’s history have proved as momentous as any over the last 125 years. Since 2013 the library has seen another failed levy vote, changes in library service, closures for the 2016 flood, additional hours open to respond to the 2019 polar vortex, and more. In 2020, the library responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 derecho.

“There are times in the last few years where it has felt like we’ve lived a lifetime in a few short months,” Library Director Dara Schmidt said. But along with the challenges, the library has checked out millions of books, hosted hundreds of thousands of patrons at programs – both in person and virtual and been an essential place for the community to come together.

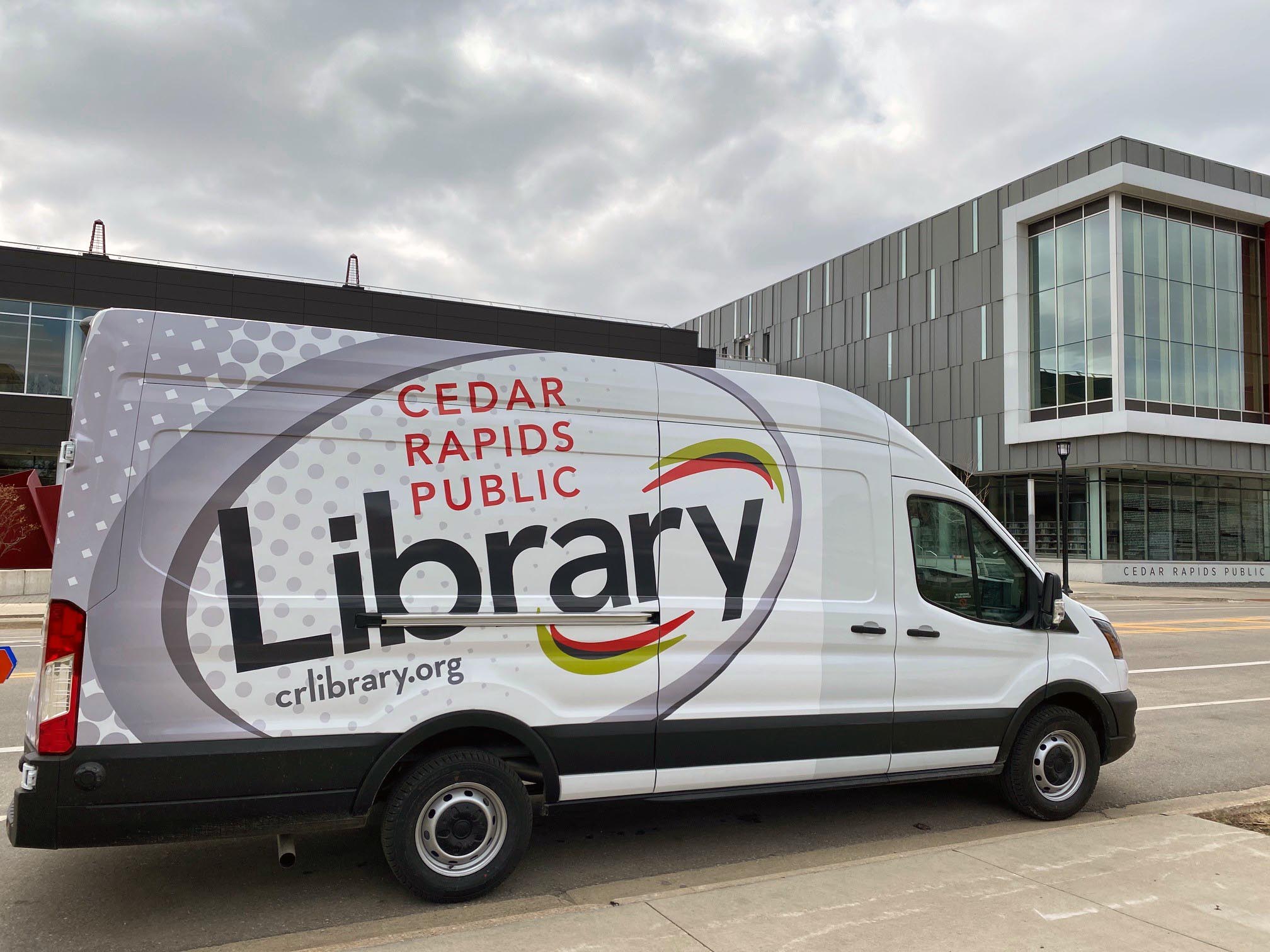

The library is also looking to the future. In 2021, the Mobile Technology Lab arrived. Instead of a traditional bookmobile, the library’s new van is loaded with technology, from laptops to 3D printers to robots designed to help kids learn coding.

Recognizing the importance of the Ladd Library to the community, library leaders are also exploring creating a permanent location on the city’s west side.

Whatever the future brings, the focus will remain the same as it has since the day the library opened – to connect people to information, experiences, and services that enhance their quality of life so our community can learn, enjoy, and thrive.

The guidebook to the road ahead was written for the library by the leaders of the past 125 years, women like Ada Van Vechten, Virginia Doge, Gladys Rice, and Evelyn Zerzanek.

“These library leaders believed in Cedar Rapids. They believed in a free, open library that served as a beacon of literacy to all who seek knowledge and understanding. They saw that a library was an essential community resource that could help our city,” Schmidt said.

“It’s hard to imagine what the next 125 years could possibly bring, but our library will stand the test of time. We will heed the call to provide free access to resources and be open to all. We will find ways to meet people where they are. We will support our children and instill a love of books and reading. We will be a community resource in times of strife. We will remain committed to the timeless pillars of literacy, access and inclusion.”